RPC (TOCS 84) 论文阅读

Implementing Remote Procedure Calls

Introduction

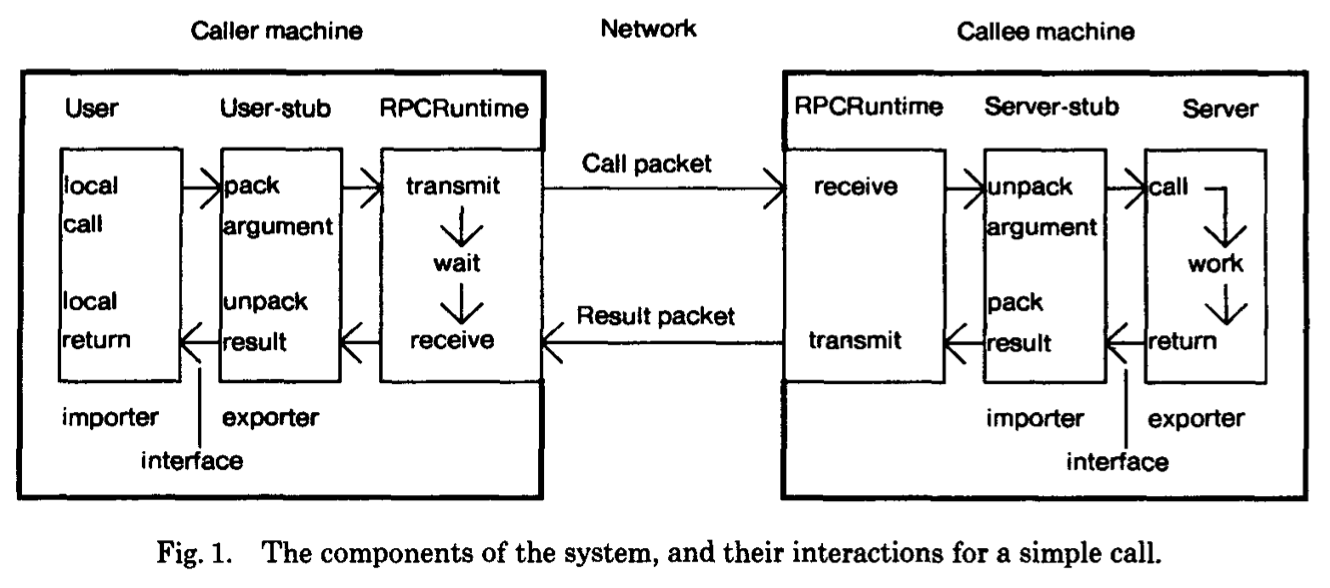

Major issues facing the designer of an RPC facility include: the precise semantics of a call in the presence of machine and communication failures; the semantics of address-containing arguments in the (possible) absence of a shared address space; integration of remote calls into existing (or future) programming systems; binding (how a caller determines the location and identity of the callee); suitable protocols for transfer of data and control between caller and callee; and how to provide data integrity and security (if desired) in an open communication network.

Our hope is that by providing communication with almost as much ease as local procedure calls, people will be encouraged to build and experiment with distributed applications. RPC will, we hope, remove unnecessary difficulties, leaving only the fundamental difficulties of building distributed systems: timing, independent failure of components, and the coexistence of independent execution environments.

A principle that we used several times in making design choices isthat the semantics of remote procedure calls should be as close as possible to those of local (single-machine) procedure calls. For example, we chose to have no time-out mechanism limiting the duration of a remote call(in the absence of machine or communication failures), whereas most communication packages consider this a worthwhile feature. Our argument is that local procedure calls have no time-out mechanism, and our languages include mechanisms to abort an activity as part of the parallel processing mechanism. Designing a new time-out arrangement just for RPC would needlessly complicate the programmer’s world.

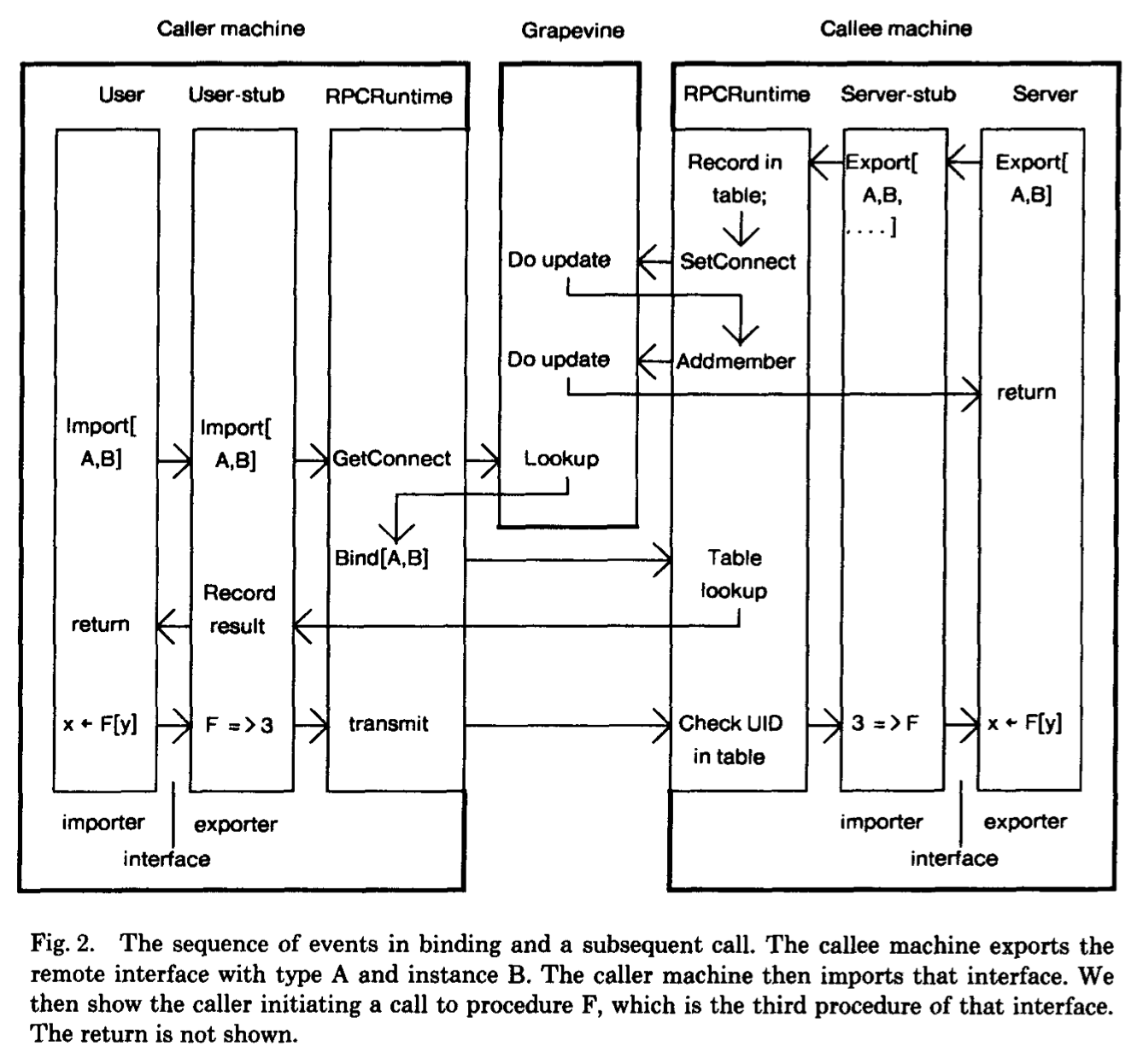

Binding

There are two aspects to binding which we consider in turn. First, how does a client of the binding mechanism specify what he wants to be bound to? Second, how does a caller determine the machine address of the callee and specify to the callee the procedure to be invoked? The first is primarily a question of naming and the second a question of location.

There are two parts to the name of an interface: the type and the instance. For example, the type of an interface might correspond to the abstraction of “mail server,” and the instance would correspond to some particular mail server selected from many.

PACKET-LEVEL TRANSPORT PROTOCOL

后略