XRP (OSDI 22) 论文阅读

XRP: In-Kernel Storage Functions with eBPF

Abstract

We present XRP, a framework that allows applications to execute user-defined storage functions, such as index lookups or aggregations, from an eBPF hook in the NVMe driver, safely bypassing most of the kernel’s storage stack.

Introduction

Complete kernel bypass (SPDK): force applications to imple- ment their own file systems, to forgo isolation and safety, and to poll for I/O completion which wastes CPU cycles when I/O utilization is low; suffer from high average and tail latencies and severely reduced throughput when the schedulable thread count exceeds the number of available cores.

BPF is an OS-supported mechanism that ensures isolation, does not lead to low utilization due to busy-waiting, and allows a large number of threads or processes to share the same core, leading to better overall utilization.

In order to maximize its performance benefit, XRP uses a hook in the NVMe driver’s interrupt handler, thereby bypassing the kernel’s block, file system and system call layers. This allows XRP to trigger BPF functions directly from the NVMe driver as each I/O completes, enabling quick resubmission of I/Os that traverse other blocks on the storage device.

Background and Motivation

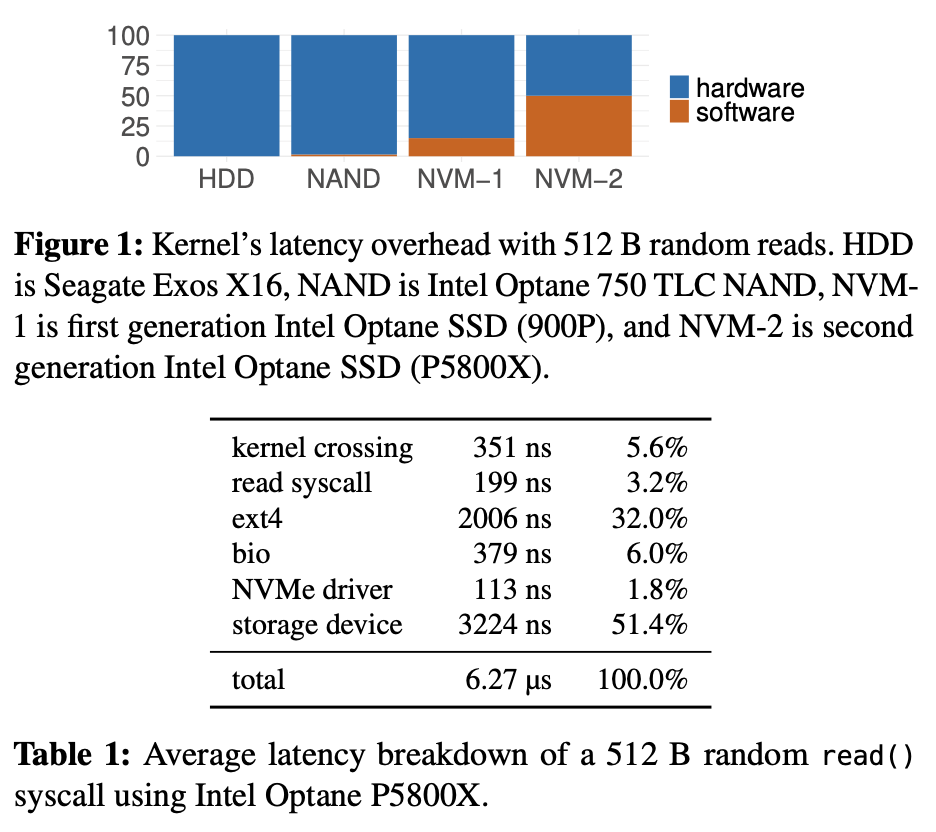

Software is now the storage bottleneck:

Design Callenges and Principles

- Challenge 1: address translation and security.

- the BPF function could access any block on the device, including blocks that belong to a file that the user does not have permissions to access.

- Challenge 2: concurrency and caching.

- A write issued from the file system will only be reflected in the page cache, which is not visible to XRP. In addition, any writes that modify the layout of the data structure (e.g., modify the pointers to the next block) that are issued concurrently to read requests could lead XRP to accidentally fetch the wrong data. Both of these could be addressed by locking, but accessing locks from within the NVMe interrupt handler may be expensive.

- Observation: most on-disk data structures are stable, e.g. LSM trees.

- Design principles.

- One file at a time: only issue chained resubmission on a single file.

- Stable data structures: whose layout (i.e. pointers) remain immutable for a long period of time (i.e. seconds or more); do not plan to support operations that require locks during the traversal or iteration of data structures.

- User-managed caches: 不能有 os page cache

- Slow path fallback (best-effort)

XRP Design and Implementation

暂略

Case Studies

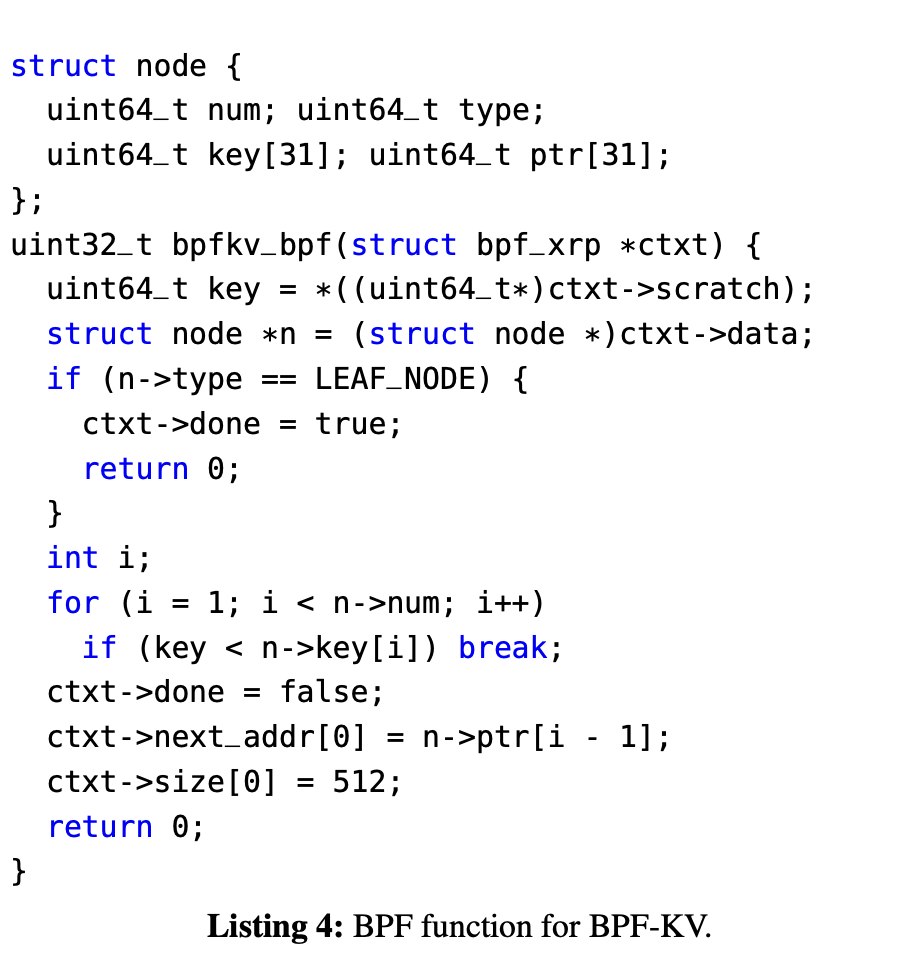

BPF-KV 这个比较有意思,如下:

- BPF-KV is designed to store a large number of small objects and to provide good read performance even under uniform access patterns. BPF-KV uses a B+-tree index to find the location of objects, and the objects themselves are stored in an unsorted log. For simplicity, BPF-KV uses fixed-sized keys (8 B) and values (64 B).

- Consider the case where BPF-KV is used to store 10 billion 64 B objects. In BPF-KV’s index, each node is 512 B (matching the access granularity of the Optane SSD); hence, the tree has a fanout of 31 (i.e. each internal node can store pointers to 31 children). Therefore, 10 billion objects would require an index with 8 levels. Fitting 6 index levels in DRAM is expensive and would require 14 GB, while fitting 7 levels or more becomes prohibitively expensive (437 GB of DRAM or more). So, to support a large number of keys, BPF-KV would require at the minimum 3-4 I/Os from storage for each lookup, including a final I/O to fetch the actual key-value pair from disk.

- Also note that having a hard memory budget for caching the index is common in many real-world key-value stores, since the index cache often competes with other parts of the system that need memory, such as filters and the object cache.

评价

use case 到底够不够广泛我不确定;software overhead 能看见的、算足够大的场景可能也就 Optane P5800X 了;assumption 有点多,比如 target static data structures,感觉有点困难。